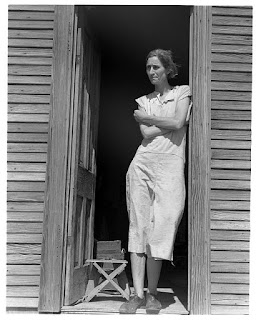

The rapid-fire text of Valhalla, with its constant shifting (and overlapping) of time and space, requires a streamlined set - yet the difference between its two main locales (Bavaria and the mythical Dainsville, Texas) is also central to its meaning and action. And therein lies one of the play's theatrical challenges: making real for the audience the phenomenal distance between the creature comforts of Ludwig II and James Avery, Paul Rudnick's fictional gay boy growing up in Texas in the 1930s. Perhaps the photograph above will help make the contrast clearer - by the famous Dorothea Lange, it's a portrait of a migrant farmer's wife in the doorway of her home near Childress, Texas, in 1938 (her three children are inside). Could this be James Avery's mother (compare and contrast Marie of Prussia, Ludwig's mother, below)?

The rapid-fire text of Valhalla, with its constant shifting (and overlapping) of time and space, requires a streamlined set - yet the difference between its two main locales (Bavaria and the mythical Dainsville, Texas) is also central to its meaning and action. And therein lies one of the play's theatrical challenges: making real for the audience the phenomenal distance between the creature comforts of Ludwig II and James Avery, Paul Rudnick's fictional gay boy growing up in Texas in the 1930s. Perhaps the photograph above will help make the contrast clearer - by the famous Dorothea Lange, it's a portrait of a migrant farmer's wife in the doorway of her home near Childress, Texas, in 1938 (her three children are inside). Could this be James Avery's mother (compare and contrast Marie of Prussia, Ludwig's mother, below)?

Saturday, March 31, 2007

Meanwhile, back in Dainsville

The rapid-fire text of Valhalla, with its constant shifting (and overlapping) of time and space, requires a streamlined set - yet the difference between its two main locales (Bavaria and the mythical Dainsville, Texas) is also central to its meaning and action. And therein lies one of the play's theatrical challenges: making real for the audience the phenomenal distance between the creature comforts of Ludwig II and James Avery, Paul Rudnick's fictional gay boy growing up in Texas in the 1930s. Perhaps the photograph above will help make the contrast clearer - by the famous Dorothea Lange, it's a portrait of a migrant farmer's wife in the doorway of her home near Childress, Texas, in 1938 (her three children are inside). Could this be James Avery's mother (compare and contrast Marie of Prussia, Ludwig's mother, below)?

The rapid-fire text of Valhalla, with its constant shifting (and overlapping) of time and space, requires a streamlined set - yet the difference between its two main locales (Bavaria and the mythical Dainsville, Texas) is also central to its meaning and action. And therein lies one of the play's theatrical challenges: making real for the audience the phenomenal distance between the creature comforts of Ludwig II and James Avery, Paul Rudnick's fictional gay boy growing up in Texas in the 1930s. Perhaps the photograph above will help make the contrast clearer - by the famous Dorothea Lange, it's a portrait of a migrant farmer's wife in the doorway of her home near Childress, Texas, in 1938 (her three children are inside). Could this be James Avery's mother (compare and contrast Marie of Prussia, Ludwig's mother, below)?

The Bachelor

Given his later excesses, it's easy to forget that at the start of his reign, Ludwig was quite popular (and he never entirely lost his public following). The coronation portrait by Ferdinand von Piloty (at left) gives some idea why: in his general's uniform and flowing coronation robes, the young Ludwig looks quite dashing (you can make out his crown in the shadows to his left). It's easy to see how the Empress of Austria might have nicknamed him "The Eagle," and it's no wonder eligible bachelorettes flocked to his court for a chance to become his queen.

Given his later excesses, it's easy to forget that at the start of his reign, Ludwig was quite popular (and he never entirely lost his public following). The coronation portrait by Ferdinand von Piloty (at left) gives some idea why: in his general's uniform and flowing coronation robes, the young Ludwig looks quite dashing (you can make out his crown in the shadows to his left). It's easy to see how the Empress of Austria might have nicknamed him "The Eagle," and it's no wonder eligible bachelorettes flocked to his court for a chance to become his queen.

All about his mother

Ludwig's mother was Marie of Prussia (so it's interesting that he so quickly submitted to Prussia's military will; see post below). She married Ludwig's father, Maximilian II, at 17 (he was twice her age), and gave birth to Ludwig at 19; she was also her husband's cousin. Marie was considered a socially engaged monarch, and was well-liked by Bavaria's Catholics, even though she herself was an Evangelical Protestant (not quite like today's evangelicals, however; those of Marie's day were dedicated to personal salvation and piety, and such social causes as temperance and abolitionism). While no intellectual - she once wondered aloud why anyone would spend time reading - Marie nevertheless revived the dormant Bavarian Women's Association, a service organization which eventually was taken over by the Red Cross. She had the reputation of being a well-meaning, but distant, mother - by most accounts, Ludwig found what motherly affection he came by from his governess (not dramatized in Valhalla), Sybille Meilhaus. Meanwhile Ludwig's father doted on his brother Otto, who was considered a far happier child than Ludwig, who even as a boy was perceived as inclined to romantic melancholy. To "correct" this tendency, his governess was replaced by a strict military tutor when Ludwig was nine (tellingly, he remained in touch with her for the rest of his life). After Maximilian's death, Marie converted to Catholicism, at first living with Ludwig in the castle her husband had built for them. But as Ludwig grew more eccentric, she slowly withdrew, spending more and more of her time at her own estate in the Alps. She outlived Ludwig by three years.

Ludwig's mother was Marie of Prussia (so it's interesting that he so quickly submitted to Prussia's military will; see post below). She married Ludwig's father, Maximilian II, at 17 (he was twice her age), and gave birth to Ludwig at 19; she was also her husband's cousin. Marie was considered a socially engaged monarch, and was well-liked by Bavaria's Catholics, even though she herself was an Evangelical Protestant (not quite like today's evangelicals, however; those of Marie's day were dedicated to personal salvation and piety, and such social causes as temperance and abolitionism). While no intellectual - she once wondered aloud why anyone would spend time reading - Marie nevertheless revived the dormant Bavarian Women's Association, a service organization which eventually was taken over by the Red Cross. She had the reputation of being a well-meaning, but distant, mother - by most accounts, Ludwig found what motherly affection he came by from his governess (not dramatized in Valhalla), Sybille Meilhaus. Meanwhile Ludwig's father doted on his brother Otto, who was considered a far happier child than Ludwig, who even as a boy was perceived as inclined to romantic melancholy. To "correct" this tendency, his governess was replaced by a strict military tutor when Ludwig was nine (tellingly, he remained in touch with her for the rest of his life). After Maximilian's death, Marie converted to Catholicism, at first living with Ludwig in the castle her husband had built for them. But as Ludwig grew more eccentric, she slowly withdrew, spending more and more of her time at her own estate in the Alps. She outlived Ludwig by three years.

Wednesday, March 28, 2007

Lost inside a diamond . . .

At the climax of Valhalla, Paul Rudnick offers a kind of synthesis of Ludwig's palaces rather than any kind of accurate tour. James and Henry Lee first visit the Schloss Linderhof, describing it as "a huge, demented wedding cake" and venturing into its famous underground "Venus grotto" (see post below). They later wander over to Neuschwanstein; in between, however, they seem to wake up in the Herrenchiemsee Neues Schloss ("New Palace"), Ludwig's "recreation" of Versailles (Ludwig seemed to divide his time between idolizing the mythical Lohengrin and the all-too-real Louis XIV).

This is physically impossible, as the Herrenchiemsee, as it is usually known, is on an island in the middle of the largest lake in Bavaria, and is only accessible by ferry. But what the hey - since Rudnick plays relentlessly with time, I suppose he can play with space, too. The Herrenchiemsee never reached the size of Versailles - only the central portion of the initial design, by Christian Jank, Franz Seitz, and Georg Dollman, was built - but it is obviously an imitation of the Sun King's palace, and features a similar (though not nearly as extensive) park, replete with baroque fountains and gardens. One feature of the Neues Schloss, however, actually surpassed in size its model at Versailles - the Hall of Mirrors (above). In Valhalla, the characters describe it as "like being lost inside a diamond," and the ghost of Marie Antoinette herself appears to compliment Ludwig on his creation.

This is physically impossible, as the Herrenchiemsee, as it is usually known, is on an island in the middle of the largest lake in Bavaria, and is only accessible by ferry. But what the hey - since Rudnick plays relentlessly with time, I suppose he can play with space, too. The Herrenchiemsee never reached the size of Versailles - only the central portion of the initial design, by Christian Jank, Franz Seitz, and Georg Dollman, was built - but it is obviously an imitation of the Sun King's palace, and features a similar (though not nearly as extensive) park, replete with baroque fountains and gardens. One feature of the Neues Schloss, however, actually surpassed in size its model at Versailles - the Hall of Mirrors (above). In Valhalla, the characters describe it as "like being lost inside a diamond," and the ghost of Marie Antoinette herself appears to compliment Ludwig on his creation.

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

Bavaria, Texas?

No, there's no Bavaria, Texas - but then there's no Dainsville, Texas, either. Instead, there are quite a few links between the Lone Star State and Ludwig's home, which hint at a striking similarity hidden beneath their juxtaposition in Valhalla. It goes largely unnoticed (or rather, it's been edited out of our cultural script since the two World Wars) that Germans comprise the single largest ethnic group in the U.S.; there are approximately 50 million Americans of German descent. As elsewhere in America, there was heavy German settlement in Texas - particularly in the Texas "Hill Country" - between 1848 and World War I, and today there's a similar conservative, religion-centered, and not very gay-friendly culture in both locales. Likewise, both Texas and Bavaria tend to view themselves as something like virtual nation-states within their larger countries' borders. Indeed, many Texans will tell you that "Bavaria is Germany's Texas," and some Bavarians have been known to favor cowboy hats. In the last few decades, Texans have adopted such Bavarian traditions as Oktoberfest with a vengeance; some say one of the largest Oktoberfests outside Munich is in Fredericksburg, Texas, which also hosts a German shooting festival, or Schuetzenfest. There's even a Texan dialect of German, which is now only spoken by a few septagenarians in the Hill Country west of Austin.

Did Princess Sophie really have a hump?

Playwright Paul Rudnick says she did - and gives her a charmingly rueful characterization based on her savvy sense of her own "difference" in the image-driven world of Ludwig's court. Indeed, perversely enough, it's her very awareness of her lack of conventional beauty - her incipient sense of camp - that endears her to the gay Ludwig.

Playwright Paul Rudnick says she did - and gives her a charmingly rueful characterization based on her savvy sense of her own "difference" in the image-driven world of Ludwig's court. Indeed, perversely enough, it's her very awareness of her lack of conventional beauty - her incipient sense of camp - that endears her to the gay Ludwig.But is Rudnick exaggerating what may have only been a slight abnormality? The photographic evidence for said hump is slim - of course the photos may have been doctored; but Sophie looks pretty normal above, in a photograph with Ludwig taken during their engagement. (For more images of Sophie, check here.)

Born Sophie Charlotte Augustine de Wittelsbach, Sophie was officially a Duchess of Bavaria; an alliance with Ludwig would have been a big step up, and would have put her on a nearly-equal social footing with her sister, Elisabeth, who was now Empress of Austria and had also been close friends with Ludwig. Clearly, unlike the character she inspired in Valhalla, Sophie was serious about the matrimonial sweepstakes; she married Ferdinand Philippe Marie, duc d'Alençon, in 1868, the year after she was dumped by Ludwig, and promptly had two children. So no flies on her, hump or not.

One last note about the gallant Duchesse d'Alençon. She was caught in a famous fire, at a charity bazaar in Paris in 1897; but when rescuers tried to carry her away from the flames, she insisted other women and children be saved first, stating "Because of my title I was the first to enter here, and I shall be the last to go out." Sophie perished in the subsequent inferno, at age 50.

One last note about the gallant Duchesse d'Alençon. She was caught in a famous fire, at a charity bazaar in Paris in 1897; but when rescuers tried to carry her away from the flames, she insisted other women and children be saved first, stating "Because of my title I was the first to enter here, and I shall be the last to go out." Sophie perished in the subsequent inferno, at age 50.

Monday, March 26, 2007

Inside Ludwig's Castles

When James and Henry Lee parachute behind enemy lines at the climax of Valhalla, they stumble onto (or into) two of Ludwig's castles, the Schloss Linderhof and Neuschwanstein (which are a few miles apart in southwestern Bavaria). As you can see from the following photographs, playwright Paul Rudnick has hardly exaggerated the extravagance of these castles' interiors (although in general, Neuschwanstein is underdecorated; only fourteen rooms, on the third and fourth floors, were completed before Ludwig's death; the first and second floors are largely bare brick to this day).

Neuschwanstein is comprised of a gatehouse, a "Bower," the Knight's House with a square tower, and a Palas, or citadel (above), with two towers to the Western end. On the exterior, it is a fanciful pastiche of medieval and Romanesque elements; its interior, however, was intended as an even more flamboyant evocation of the chivalric ethos of Richard Wagner's operas.

The rooms within the Palas that were finished by Ludwig are so overdecorated as to be almost overwhelming; the Throne Room (above) in particular was intended to resemble the legendary Grail-Hall of Parsifal (father of Lohengrin), and so was designed in an elaborate Byzantine style by Eduard Ille and Julius Hofmann. Inspired by the Hagia Sophia, the two-story Throne Room was only completed in the year of the king's death; the throne itself was never made.

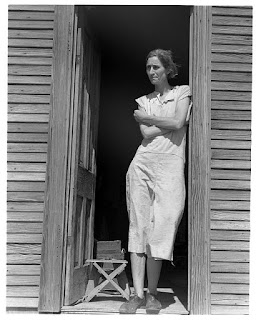

The Grotto, which was not underground, as one might expect, but was located between Ludwig's living room and his study, was one of the most unusual rooms in Neuschwanstein, and was used by the increasingly-isolated king as a refuge in which to indulge his melancholy moods. Its artificial stalactites were built of oakum and plaster-of-Paris by the famed landscape sculptor Dirrigl of Munich. Dirrigl had already built a far more extragant grotto in the park of the Schloss Linderhof. This artificial lake was designed as a kind of real-life stage set for the "Venus Grotto" scene from Wagner's Tannhäuser (see below). It is in this underground boudoir, with its far more erotic atmosphere, that James and Henry Lee first encounter Ludwig's legacy in Valhalla.

The Grotto, which was not underground, as one might expect, but was located between Ludwig's living room and his study, was one of the most unusual rooms in Neuschwanstein, and was used by the increasingly-isolated king as a refuge in which to indulge his melancholy moods. Its artificial stalactites were built of oakum and plaster-of-Paris by the famed landscape sculptor Dirrigl of Munich. Dirrigl had already built a far more extragant grotto in the park of the Schloss Linderhof. This artificial lake was designed as a kind of real-life stage set for the "Venus Grotto" scene from Wagner's Tannhäuser (see below). It is in this underground boudoir, with its far more erotic atmosphere, that James and Henry Lee first encounter Ludwig's legacy in Valhalla.

The Venus Grotto at Schloss Linderhof.

Sunday, March 25, 2007

Lohengrin and the Holy Grail

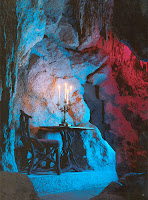

Lohengrin (at left, from a nineteenth century postcard) first appears in the written record as "Loherangrin," the son of Parzival, the Grail King, in the epic Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach (1170-1220). The Knight of the Swan story was part of a long oral tradition associated with Godfrey of Bouillon, but von Eschenbach was the first to tie the tale to the Arthurian legend of the Holy Grail. In this version of the story, Loherangrin serves his father as one of the Grail Knights, who are sent out in secret to guard kingdoms that have lost their protectors. Loherangrin is eventually called to this duty in Brabant, where the duke has died without a male heir. The duke's daughter Elsa fears the kingdom will be lost, but Loherangrin arrives in a boat pulled by a swan and offers to defend her, though he warns that she must never ask his name. They fall in love and eventually wed, but one day Elsa asks what she knows is verboten. The Swan Knight answers, but then regretfully steps back onto his boat, never to return.

Lohengrin (at left, from a nineteenth century postcard) first appears in the written record as "Loherangrin," the son of Parzival, the Grail King, in the epic Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach (1170-1220). The Knight of the Swan story was part of a long oral tradition associated with Godfrey of Bouillon, but von Eschenbach was the first to tie the tale to the Arthurian legend of the Holy Grail. In this version of the story, Loherangrin serves his father as one of the Grail Knights, who are sent out in secret to guard kingdoms that have lost their protectors. Loherangrin is eventually called to this duty in Brabant, where the duke has died without a male heir. The duke's daughter Elsa fears the kingdom will be lost, but Loherangrin arrives in a boat pulled by a swan and offers to defend her, though he warns that she must never ask his name. They fall in love and eventually wed, but one day Elsa asks what she knows is verboten. The Swan Knight answers, but then regretfully steps back onto his boat, never to return.In 1848 Richard Wagner adapted the tale into his wildly popular opera Lohengrin,the work through which the story is best (perhaps solely) known today. In the opera, Lohengrin appears on his favorite mode of transport to defend Princess Elsa from the false accusation of killing her brother (who turns out to be alive and well at the end of the opera). Intriguingly, Wagner extends the theme of the Holy Grail, and its symbolism of masculine purity, further into the story by adding an explanation for Lohengrin's keeping his true identity in the closet: the Grail, recovered by Lohengrin's father, imbues the Knight of the Swan with mystical powers that can only be maintained if their source remains unspoken. The most famous piece from Lohengrin is the "Bridal Chorus" (now familiar as "Here Comes the Bride"), which accompanies the marriage of Lohengrin and Elsa; one of the shorter Wagnerian works, the opera remains a staple of the modern stage.

Robert Wilson's recent production of Lohengrin for the Metropolitan Opera.

Ludwig, Wagner, Swans, and Castles

One of Ludwig's first royal acts was to become an official patron of Wagner, and he invited the composer to visit his court, despite Wagner’s controversial political past, and what was perceived as the “radicalism” of his operas.

One of Ludwig's first royal acts was to become an official patron of Wagner, and he invited the composer to visit his court, despite Wagner’s controversial political past, and what was perceived as the “radicalism” of his operas. Wagner’s Lohengrin, with its Swan Knight hero, had particularly captured the young king’s fancy, and no wonder - his childhood home, Schloss Hohenschwangau (below), was built by Ludwig's father, Maximilian, on the remains of the fortress Schwanstein (or “Swan Stone” Castle), which was first mentioned in records from the 12th century. Legend had it that a family of knights was responsible for its construction. After the demise of their order in the 16th century, the fortress changed hands several times, and had fallen into ruin by the time Maximilian ascended the throne.

Schloss Hohenschwangau, built on the ruins of the legendary Schwanstein.

Ludwig's awareness that his home was built on the ruins of this legendary fortress would eventually combine with his obsession with Lohengrin to produce his greatest architectural folly - the castle later known as Neuschwanstein ("New Swan Stone" Castle). Ludwig outlined his vision in a letter to Wagner, dated 13 May 1868; "It is my intention to rebuild the old castle ruin at Hohenschwangau near the Pollat Gorge in the authentic style of the old German knights' castles...the location is the most beautiful one could find, holy and unapproachable, a worthy temple for the divine friend who has brought salvation and true blessing to the world." The foundations of the building were laid on September 5, 1869 - although Ludwig would not live to see the project completed. Neuschwanstein was designed by Christian Jank, a theatrical set designer, which explains much of its fantastic decoration. Despite its faux-medieval appearance, however, the castle was built on a steel frame and came outfitted with every modern convenience. During Ludwig's life, the building was known as "New Hohenschwangau Castle"; it was only after his death that the name "Neuschwanstein" became popular, melding Ludwig's identity with that of the Swan Knights.

Neuschwanstein today.

King Ludwig II, Part I

A central figure in Valhalla,King Ludwig II of Bavaria was born in 1845, the son of King Maximilian II of Bavaria and Princess Marie of Prussia. He was extremely spoiled as a child, and constantly reminded of his royal power; but he was also often subjected to ruthless regimens of exercise and study. The happiest days of his childhood were spent at Lake Starnberg (the eventual site of his death), and Schloss Hohenschwangau, the castle built by his father in the foothills of the Alps.

A central figure in Valhalla,King Ludwig II of Bavaria was born in 1845, the son of King Maximilian II of Bavaria and Princess Marie of Prussia. He was extremely spoiled as a child, and constantly reminded of his royal power; but he was also often subjected to ruthless regimens of exercise and study. The happiest days of his childhood were spent at Lake Starnberg (the eventual site of his death), and Schloss Hohenschwangau, the castle built by his father in the foothills of the Alps.Teenaged Ludwig became best friends with (and possibly the lover of) his aide de camp, the handsome aristocrat and sometime actor Paul Maximilian Lamoral, a scion of the wealthy Thurn and Taxis dynasty. The two young men rode together, read poetry aloud, and staged excerpts from the operas of their idol, Richard Wagner. Their relationship lapsed when Paul eventually became more interested in (or at least began courting) young women. During these years Ludwig began a lifelong friendship with his cousin Duchess Elisabeth, who eventually married Franz Joseph to become Empress of Austria. The two teenagers loved nature and poetry, and nicknamed each other “the Eagle” (Ludwig) and “the Seagull” (Elisabeth).

In 1864, King Maximilian died, and Ludwig inherited the throne at 18. He took the royal apartments in Schloss Hohenschwangau as his own, but did not displace his mother - as he never married, she retained her customary rooms in the castle. By 1867, Ludwig had become engaged to Princess Sophie, his cousin and Empress Elisabeth's younger sister, but after repeatedly postponing the wedding, Ludwig cancelled the engagement that October. Ludwig never married - instead he was linked romantically to a number of men, including his chief equerry Richard Hornig, Hungarian theatre star Josef Kainz, and courtier Alfons Weber. (Sophie eventually married Ferdinand Philippe Marie, duc d'Alençon, but died some twenty years later in a fire which destroyed the Paris Charity Bazaar.)

That same year, Ludwig underwent (and failed) his most serious test as a monarch; he sided with Austria against Prussia in the Seven Weeks' War, and was forced to accept a mutual defense treaty with Prussia after Austria's defeat. Under the terms of this treaty, Bavaria joined with Prussia against France in the Franco-Prussian War. Ludwig received some concessions in return for his support, but essentially he had lost his independence. Stripped of true responsibility for his kingdom, Ludwig began to recede further into a life of royalist fantasy. He was only 22.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)