Friday, April 20, 2007

The Globe Review

Some actors have pleaded their desire to be insulated from all reviews, positive or negative. But I can't resist linking to the Globe's. Sandy MacDonald weighs in here.

Tuesday, April 17, 2007

The reviews are in!

Maureen Aducci, Rick Park and Brian Quint work that sacred/profane thang in Valhalla.

The first reviews are in - and they're raves. Jennifer Bubriski, on www.edgeboston.com, says: "The jokes fly fast and furiously, but it’s the depth of the characters and skill of the actors that makes Valhalla theatrical paradise." And in the pages of the Boston Metro, Nick Dussault chimes in (under the headline "A Perfect Fairy Tale"):"David Miller and the Zeitgeist Stage Company turn Paul Rudnick's comic epic . . . into a piece that is simply a joy to watch."

Monday, April 16, 2007

Opening weekend!

Our talented cast: Rick Park, Maureen Adduci, Brian Quint, Elisa MacDonald, Christopher Brophy, and Jon Ferreira

After a truly frightening dress - in which it seemed that everything that could go wrong, did - Valhalla opened last Friday, the 13th (!). But the date, surprisingly, was no jinx; instead, for the first time, the show's many costume changes and lighting/sound cues came off without a hitch. And the audience was in stitches - our trusty stage manager, Deirdre Benson, told us that audience laughter added 15 minutes to the running time! It was a shock to several actors (we'd all pretty much forgotten just how funny the play is) - but everyone was quite light on their feet, finding new beats and adjusting their rhythms to match the audience response. And both Jon and Brian brought a moving new dimension to the lead roles; for the first time a sense of heartbreaking loss seemed to hang in the air. At the final curtain, hugs were traded all around, and most of the cast (and yours truly) retired to the oh-so-elegant Sibling Rivalry to sip overpriced martinis (you must try the Pamplemousse if you're there) and trade war stories.

I could sleep it off the next day - but the cast had to rest up for two shows, at 4 and 8 (which the Globe and Phoenix attended), as well as the matinee on Sunday. It is, to be sure, an exhausting show, but it's also oh so satisfying to finally feel it play out before an audience. Valhalla has finally arrived.

Chris and Jon get acquainted with Greco-Roman Art. This scene had the straight guys in the audience hiding their eyes.

Brian (Ludwig) and Elisa (Marie Antoinette) get ready to gavotte in Seth Bodie's gorgeous costumes.

Brian (Ludwig) ascends the throne, but stays under Maureen's (the Queen's) thumb.

Thursday, April 12, 2007

Tech Week!

To paraphrase Tolstoy, every tech week is crazy in its own way - and the one for Valhalla seems to have been particularly gonzo, what with all the lighting and costume changes to track. Speaking of costumes - designer Seth Bodie has more than outdone himself in bringing both nineteenth century Bavaria and 1940s Texas to life. Here are a few cast members encountering for the first time what they get to wear:

Brian Quint as Ludwig in his brand-new crown.

Elisa MacDonald tries not to lose her head over her Marie Antoinette frock.

Brian Quint as Ludwig in his brand-new crown.

Elisa MacDonald tries not to lose her head over her Marie Antoinette frock.

Wednesday, April 11, 2007

By reason of insanity

Why, after years of eccentric behavior, was Ludwig finally declared insane and deposed by his Cabinet? The reasons were probably financial in nature. While Ludwig paid for his palaces out of his own resources, his relentless building program had dragged him deeper and deeper into debt, and the scandal of royal bankruptcy had begun to loom. In 1884 a loan had to be secured from the Bavarian State Bank to continue the work on Neuschwanstein, but rather than economize as a result, Ludwig only planned even grander projects - he had the site cleared for Castle Falkenstein, and announced Byzantine and Chinese palaces would soon follow. When Ludwig turned to his Cabinet for a second loan, however, they refused; the king responded by sending servants out to other monarchs to beg for funds, and gossip arose that he was seeking men for a crazed plan to break into banks in Berlin, Frankfurt and Paris. By 1886, it was rumored Ludwig had even begun seeking new ministers for his Cabinet, and the ruling clique decided it had to act.

Why, after years of eccentric behavior, was Ludwig finally declared insane and deposed by his Cabinet? The reasons were probably financial in nature. While Ludwig paid for his palaces out of his own resources, his relentless building program had dragged him deeper and deeper into debt, and the scandal of royal bankruptcy had begun to loom. In 1884 a loan had to be secured from the Bavarian State Bank to continue the work on Neuschwanstein, but rather than economize as a result, Ludwig only planned even grander projects - he had the site cleared for Castle Falkenstein, and announced Byzantine and Chinese palaces would soon follow. When Ludwig turned to his Cabinet for a second loan, however, they refused; the king responded by sending servants out to other monarchs to beg for funds, and gossip arose that he was seeking men for a crazed plan to break into banks in Berlin, Frankfurt and Paris. By 1886, it was rumored Ludwig had even begun seeking new ministers for his Cabinet, and the ruling clique decided it had to act.

A drawing of Ludwig's planned Chinese palace.

The Cabinet settled on a plan to depose Ludwig for constitutional reasons (rather than through a coup d'etat), by removing him due to his unfitness to govern, by reason of insanity. One problem with this plan was that Ludwig's brother Otto, next in line to the throne, was clearly incurably mad, and had been institutionalized since 1872. Ludwig's uncle, Prince Luitpold, however, agreed to act as Regent, but only on the condition that he was convinced Ludwig was truly unfit to govern. Thus a team of four eminent psychiatrists, headed by Dr Berhard von Gudden - the leading German psychiatrist of the day - was chartered to compile an official report on Ludwig, and Count von Holnstein, Ludwig's Master the Horse, set about collecting stories and gossip about the king.

There was no shortage of lurid rumors. Ludwig's public appearances were bizarre enough - he often chattered to himself, pulling his beard, and was so shy on state occasions that he sometimes hid behind screens of flowers. The king was also known to repeatedly hug various pillars and architectural features of his castles, and enjoyed dressing up as Lohengrin and other medieval heroes. But servants also told tales of beatings, children's games, and stableboys dancing naked before the king in the moonlight (!). The report convinced Prince Luitpold, and a mission was sent to Neuschwanstein to arrest the king.

Appropriately enough, the mission ended in a debacle - alerted to its approach, peasants loyal to Ludwig swarmed the castle, and a baroness in love with the king caused a scene by brandishing her parasol menacingly at the gate. Loyalists tried to persuade Ludwig to flee over the Alps, but he refused; the king then attempted to issue a proclamation protesting the mission, but it was suppressed by the government. From Berlin, Bismarck - who was only partly sympathetic to the Cabinet - advised Ludwig that to hold onto the throne, he must show himself to the people, but the neurotic Ludwig refused this course of action, too. When a second mission arrived at Neuschwanstein, he submitted to arrest in his bedroom (below), and was declared insane. The king was then transported to Berg Castle on Lake Starnberg.

Tuesday, April 10, 2007

Back to Bavaria, Texas

Ludwig II never laid the cornerstone for his last fantasy, Castle Falkenstein - but over a century after his death, one has sprung up in the Texas Hill Country, 50 miles west of Austin. The castle's owners, Terry and Kim Young, were inspired to build it by a visit to Neuschwanstein, in which they learned of the Mad King's unrealized plans. To arrange your wedding there, go to www.falkensteincastle.com (packages begin at $5,995).

Ludwig II never laid the cornerstone for his last fantasy, Castle Falkenstein - but over a century after his death, one has sprung up in the Texas Hill Country, 50 miles west of Austin. The castle's owners, Terry and Kim Young, were inspired to build it by a visit to Neuschwanstein, in which they learned of the Mad King's unrealized plans. To arrange your wedding there, go to www.falkensteincastle.com (packages begin at $5,995).

A modern-day Ludwig and Sophie at Castle Falkenstein, Texas.

Genius - or kitsch?

Sleeping Beauty's Castle at Disneyland.

There was a deep irony in Ludwig's sponsorship of Wagner - he adored the composer's operas only for their backward-looking plots and themes, not their musical and dramatic innovations. In short, he was a patron who contributed to the advance of his chosen art only accidentally. This shortcoming is even clearer in Ludwig's architectural pursuits: gorgeous as his castles may be, they are essentially sentimental attempts to revive lost styles, or even copy specific older buildings.

Of course the late Victorian period was generally one in which architects revived and combined Gothic and Romanesque elements into lively pastiches; they usually did so, however, with an eye toward creating new, exotic juxtapositions. Indeed, the most talented architects were already creating new forms to match the technology used to build Neuschwanstein (above); even as the castle was completed, for instance, Louis Sullivan had begun building his famous skyscrapers in Chicago, and Frank Lloyd Wright had taken on his first clients. Ludwig, however, like a child who cries out to hear the same story over and over, had only attempted to recreate lost idylls.

Of course the late Victorian period was generally one in which architects revived and combined Gothic and Romanesque elements into lively pastiches; they usually did so, however, with an eye toward creating new, exotic juxtapositions. Indeed, the most talented architects were already creating new forms to match the technology used to build Neuschwanstein (above); even as the castle was completed, for instance, Louis Sullivan had begun building his famous skyscrapers in Chicago, and Frank Lloyd Wright had taken on his first clients. Ludwig, however, like a child who cries out to hear the same story over and over, had only attempted to recreate lost idylls.  This essential flight from reality makes the one case in which he was influential highly (if ironically) appropriate - Neuschwanstein provided the model for Sleeping Beauty's Castle at the entrance to Fantasyland in Disneyland (above); one synthetic castle inspired another.

This essential flight from reality makes the one case in which he was influential highly (if ironically) appropriate - Neuschwanstein provided the model for Sleeping Beauty's Castle at the entrance to Fantasyland in Disneyland (above); one synthetic castle inspired another. (Indeed, Ludwig would have topped anything Disney could have come up with if he had lived to build his next project, Castle Falkenstein - at right, in a sketch by Christopher Jank.)

This is what keeps Ludwig out of the architectural history books - and what makes Valhalla a tragicomedy, rather than a tragedy. There's something grand about Ludwig's folly, but also something silly - in the end, he was not a real artist, as he refused to genuinely engage with his own situation or time. He used the arts not to explore but to assuage, comfort, and aggrandize himself and his ego. In a way, of course, this only exposed his weaknesses all the more - his grandeur was faintly ridiculous, and somehow lonely and sad.

Neuschwanstein in winter.

Neuschwanstein in winter.

Monday, April 9, 2007

The break-up

Ludwig's lavish wedding coach was never used.

The date for the Ludwig and Sophie's wedding was first set for August, 1867, but as summer approached it was changed to October 12th - with the excuse that this was the date both Ludwig I and Max II had married. It was clear, however, that the relationship was falling apart; the couple looked unhappy, and Ludwig often left the entertainments they attended early, and alone. The king even confided to the Court Secretary that he would rather drown himself than marry.

At the time, Wagner was his closest confidante - in fact, the court, feeling the composer's influence over the king was unhealthy, had forced him to decamp to Switzerland. As the wedding date drew near, Ludwig wrote to his friend, "Oh, if only I could be carried on a magic carpet to you . . . at dear, peaceful Tribschen (Wagner's house in Lucerne, Switzerland, where Ludwig had installed him) - even for an hour or two. What I would give to be able to do that!" Meanwhile, humiliated and despondent, Sophie sent Ludwig a letter offering him his freedom; he responded by once more postponing the wedding - indefinitely.

Finally Sophie's father demanded Ludwig set a date at the end of November, or withdraw his proposal. Ludwig immediately did just that, writing in his diary, "Sophie is finished with. The gloomy picture vanishes. I longed for freedom, I thirsted for freedom, to wake from this horrible nightmare."

Sophie quickly moved on; within a few months she was engaged to the Duke of Alençon, whom she would marry the next year and bear two children. Meanwhile the distraught king fled to his childhood home, Hohenschwangau, and wrote to his beloved Wagner: "I write these lines sitting in my cozy gothic bow-window, by the light of my lonely lamp, while outside the blizzard rages. It is so peaceful here, this silence is stimulating, whereas in the clamour of the world I feel absolutely miserable. Thank God I am alone at last. My mother is far away, as is my former bride, who would have made me unspeakably unhappy. Before me stands a bust of the one, true Friend whom I shall love until death. . . If only I had the opportunity to die for you . . ."

Friday, April 6, 2007

Ludwig, the musical????

Yes, hard as it may be to believe, there is indeed "Ludwig, the Musical", or rather Ludwig II, "a unique theatrical experience in the heart of Bavaria." This 5-act extravaganza is performed in the new Festspielhaus Neuschwanstein (shades of Bayreuth!) on the shores of Lake Foegensee, below Neuschwanstein. And if that isn't meta enough for you, consider that when audiences leave the theater, they are confronted with the castle itself - truly a moment of life imitating art imitating life. Reviewers (rather in the manner of Natalie Kippelbaum) had this to say: "Pros: Hauntingly beautiful music in the tradition of Andrew Lloyd Weber; sets, scenes and performances are exceptional. Cons: It's in German; it has a sad ending."

Schwan's way

What's with all the swans? One actor in Valhalla asked me the other day. I wish I had a good answer - aside from the fact that because of its obvious beauty and elegance, the swan had long been a favored emblem of European nobility; nobles across Britain, Germany and France wanted swans in their moats and peacocks pecking at their lawns. There seems to have been a "perfect storm" of swan imagery around Ludwig II, however. The name of his childhood home, Hohenschwangau, literally translates as "High Swan District," and it overlooked the Schwansee (yes, "Swan Lake"), a natural habitat for the birds (see photo below). The foundation of Hohenschwangau had also been built centuries before by the Knights of Schwangau, or the Swan Knights (see lower post); it's not so strange, having grown up in this environment, that Ludwig should have been especially drawn to the mythical Swan Knight Lohengrin.

What's with all the swans? One actor in Valhalla asked me the other day. I wish I had a good answer - aside from the fact that because of its obvious beauty and elegance, the swan had long been a favored emblem of European nobility; nobles across Britain, Germany and France wanted swans in their moats and peacocks pecking at their lawns. There seems to have been a "perfect storm" of swan imagery around Ludwig II, however. The name of his childhood home, Hohenschwangau, literally translates as "High Swan District," and it overlooked the Schwansee (yes, "Swan Lake"), a natural habitat for the birds (see photo below). The foundation of Hohenschwangau had also been built centuries before by the Knights of Schwangau, or the Swan Knights (see lower post); it's not so strange, having grown up in this environment, that Ludwig should have been especially drawn to the mythical Swan Knight Lohengrin.For a lovely 360-degree panorama of the Schwansee today, go here.

Hohenschwangau Castle at left, Schwansee at upper right.

Thursday, April 5, 2007

The "Moon King"

Ludwig sometimes styled himself "the Moon King," in deference to his idol, Louis XIV, the "Sun King." One of his favorite diversions was a lonely sleigh ride under the full moon - memorialized in the painting above by R. Wenig. If you think the gilded decoration of the sleigh in the painting is hard to believe, a similar one (with electric lamps up front) still exists at Ludwig's palace in Munich, Schloss Nymphenburg (below).

Ludwig, Wagner, Hitler, and the Jews

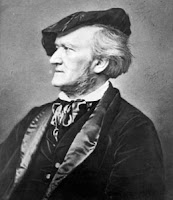

Ludwig II’s sponsorship of Richard Wagner(left) lifts him into a rarefied sphere of artistic influence – one in which only a handful of patrons (the Medici, Gertrude Stein) could claim precedence. For Wagner’s radical ideas about “music drama” – his development of the leitmotif, his extreme chromaticism, and his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total artwork,” would not only transform operatic form but also be immensely influential in the development of film music, and even in the general theory of film itself. Indeed, Wagner set all kinds or precedents, large and small; he was the first to dim the "house lights" during performances, and the first to sink the orchestra into a "pit." But all of this might not have happened without Ludwig, who rescued the composer from financial ruin, sponsored the composition and production of both Tristan and Isolde (during which Wagner met his second wife, Cosima) and the Ring cycle, and largely funded the building of the famous Bayreuth Festspielhaus (below), the international center of Wagner production to this day.

Ludwig II’s sponsorship of Richard Wagner(left) lifts him into a rarefied sphere of artistic influence – one in which only a handful of patrons (the Medici, Gertrude Stein) could claim precedence. For Wagner’s radical ideas about “music drama” – his development of the leitmotif, his extreme chromaticism, and his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or “total artwork,” would not only transform operatic form but also be immensely influential in the development of film music, and even in the general theory of film itself. Indeed, Wagner set all kinds or precedents, large and small; he was the first to dim the "house lights" during performances, and the first to sink the orchestra into a "pit." But all of this might not have happened without Ludwig, who rescued the composer from financial ruin, sponsored the composition and production of both Tristan and Isolde (during which Wagner met his second wife, Cosima) and the Ring cycle, and largely funded the building of the famous Bayreuth Festspielhaus (below), the international center of Wagner production to this day.

But Wagner would also exert a horrifying influence over twentieth century history through his notorious anti-Semitism. In 1850, he published the essay Judaism and Music, an attack on the Jewish composers Meyerbeer and Mendelssohn (ironically, but unsurprisingly, a major influence on Wagner) which developed into a wild condemnation of the Jewish people as a threat to German culture. Wagner claimed that Jews had club feet (so they could not keep proper musical time) and that as their speech was “intolerably jumbled blabber,” they could never communicate true passion; he wrote, “Only those artists who abandoned their Jewish roots - were that possible - could at all express themselves artistically.” In a highly influential passage, Wagner warned “So long as the separate art of music had a real organic life-need in it . . . there was nowhere to be found a Jewish composer.... Only when a body’s inner death is manifest, do outside elements win the power of lodgement in it—yet merely to destroy it.” In a word, German music had to be protected from the Jews.

Wagner first published these horrifying slurs anonymously, as a pamphlet (which promptly sank like a stone), but he published an expanded version under his own name while under Ludwig’s patronage, and continued to assail the Jewish people in essays and newspaper articles until his death. Incredibly, he at the same time had many Jewish friends and acquaintances, including his favorite conductor, Hermann Levi.

The entrance to Dachau, the first Nazi concentration camp, near Munich in Bavaria.

It’s debated whether or not Hitler and his associates ever read Judaism and Music – the essay was rarely reprinted, and was largely regarded as an embarrassment by progressive Wagnerites. Nevertheless, Wagner became closely identified with the Nazi movement. Hitler once claimed that "there is only one legitimate predecessor to National Socialism: Wagner.” The composer’s music was played at Nazi rallies, and the Nazi hierarchy often attended performances of his operas. Indeed, Wagner's daughter-in-law, Winifred Wagner, was an outspoken admirer of Hitler and ran the Bayreuth Festival from the death of her husband (Siegfried – surprise!) until the end of World War II, when she was unceremoniously given the boot. The identification was so complete that no Wagner opera has been performed in Israel to this day; in 2001, when the Jewish conductor Daniel Barenboim began a performance of the overture to Tristan and Isolde in Jerusalem, there was a major outcry, and some audience members stormed out.

How are we to take, then, Natalie Kippelbaum, the nice, affectionately-stereotyped Jewish lady (and close cousin of Rudnick's film-reviewing alter ego, Libby Gelman-Waxner) who marches through Ludwig’s castles at the end of Valhalla on “Temple Beth Shalom’s Whirlwind European Adventure Castles of Bavaria plus Wine Tasting and Wienerschitzel Potpourri Tour”? Rather pointedly, Natalie even finds herself drawn to Ludwig because of music – “gorgeous, operatic music” – i.e., Wagner – that stops her cold in a suicide attempt. “And I think,” Natalie asks herself at that terrible moment, “where is that music coming from, I mean, where was it born?” Well, it was born in the mind of an anti-Semite - who, years after the fact, inadvertently has saved Natalie's life.

Paul Rudnick – a gay playwright raised in a Reform Jewish household – is here brazenly playing with some very controversial ideas: a Jewish matron in love with Wagner, and dancing the gavotte in the homeland of Hitler himself. But can the Holocaust be forgotten, if not forgiven, before the beauty of Wagner’s music and the eccentric innocence of Ludwig (who protested the composer's anti-Semitic views)? Or can Wagner's music simply be denatured of its hateful legacy?

Or is Paul Rudnick not so much attempting to challenge his audience as tease it into accepting that with the passage of time, Natalie’s attitudes may become commonplace? In a way, in fact, Mrs. Kippelbaum may represent the final triumph over Wagner’s lunatic prejudice – after all, what better way for a nice Jewish lady to refute Judaism and Music than to fall in love with Wagner's own stuff?

Bed, Bath and Beyond

Wednesday, April 4, 2007

Of mad kings and opera queens

At the end of Paul Rudnick’s hit play Jeffrey, the title character says to the audience, “I know it’s wrong to say that all gay men are obsessed with sex. Because that’s not true. All human beings are obsessed with sex. All gay men are obsessed with opera.” Rudnick returns to this idea with a vengeance in Valhalla, but in the days since Jeffrey it's become a staple of friendly Will-and-Grace-style gay stereotyping – every gay male of a certain age is expected to be obsessed with some favorite soprano (often Maria Callas). The trope has been seconded by such openly gay writers as Terrence McNally (in his Lisbon Traviata – you can now actually see a recording of that supposed operatic pinnacle on youtube), and got its academic blessing in The Queen's Throat: Opera, Homosexuality and the Mystery of Desire by Wayne Koestenbaum of Yale University. Indeed, historians have noted a long connection between gay, or at least dandified, behaviors and the opera – some 150 years ago, in fact, the aisle before the orchestra pit in London opera houses was known as “fop’s alley” for all the stylish men who congregated there.

At the end of Paul Rudnick’s hit play Jeffrey, the title character says to the audience, “I know it’s wrong to say that all gay men are obsessed with sex. Because that’s not true. All human beings are obsessed with sex. All gay men are obsessed with opera.” Rudnick returns to this idea with a vengeance in Valhalla, but in the days since Jeffrey it's become a staple of friendly Will-and-Grace-style gay stereotyping – every gay male of a certain age is expected to be obsessed with some favorite soprano (often Maria Callas). The trope has been seconded by such openly gay writers as Terrence McNally (in his Lisbon Traviata – you can now actually see a recording of that supposed operatic pinnacle on youtube), and got its academic blessing in The Queen's Throat: Opera, Homosexuality and the Mystery of Desire by Wayne Koestenbaum of Yale University. Indeed, historians have noted a long connection between gay, or at least dandified, behaviors and the opera – some 150 years ago, in fact, the aisle before the orchestra pit in London opera houses was known as “fop’s alley” for all the stylish men who congregated there.Why the connection? To Koestenbaum, himself an avowed opera queen, identifying with the diva offered gay men a vicarious emotional release they were simply denied in the straight world. In Lisbon Traviata, one character puts it this way: "Opera doesn't reject me. The real world does." Of course, it’s a little more complex than that: grand opera may trade in release, but its very core is the idea that desire must be thwarted; the great divas are always cut down, and often humiliated in the bargain – by the final curtain, the queen has been put back in her place. Indeed, a sense of that vulnerability – and incipient humiliation - is crucial to the quasi-drag queen grandeur of the true diva.

Still, as gay men have moved out of the closet, shouldn't this identification have therefore lessened, rather than grown? And there's the larger point that opera could hardly have survived with only a gay audience; clearly, plenty of straight people are opera queens, too. Perhaps everyone can relate to having their desires thwarted - and certainly operatic voices alone are enough to stir anyone's emotions (indeed, the fact that many gay men respond almost sexually to the female voice only indicates its power).

As for Ludwig – he does, indeed, seem to have been an “opera queen,” but he was certainly an unusual one. There’s little evidence, for instance, that he was obsessed with particular divas; he identified not with sopranos, or even with tenors (despite his attempts to seduce a few), but rather with the heroic roles themselves and the themes they embodied. He didn’t so much live vicariously through opera as try to turn his own life into a simulation of one. The link, perhaps, between Ludwig and today’s queens is that his favorite roles – say, Lohengrin (that's Johannes Sembach in the role above) – included an element of romantic denial, and an almost hysterical obsession with purity. A proxy for his own sense of sexual denial? Perhaps. Ludwig also fell into the trap that so many modern opera queens do - a lonely, "perfectionist" narcissism (he often watched his operas alone, in a deserted theatre). One thing the "mad king" entirely lacked, however, and that the modern opera queen is known for, is a sense of irony. Few in power, of course, are known for their self-awareness, much less their irony; but without that escape valve, opera may indeed be a path to insanity.

Monday, April 2, 2007

Shall we dance?

In Valhalla, Ludwig meets the ghost of Marie Antoinette in his Hall of Mirrors, and the pair do a quick gavotte - a dance which originated as a French folk dance (above, a Breton version), and took its name from the Gavot peasants of the Alpine Pays de Gap region. The gavotte is notated in 4/4 or 2/2 time, and in its original form, its musical phrases began in the middle of the bar, creating a half-measure upbeat. Dancers generally faced each other either in lines or a circle with joined hands, but steps varied widely, as did floor patterns and such pantomimes as bowing to the leader of the dance; a distinguishing feature of the gavotte, however, was that when moving sideways, dancers were required to cross their feet in a step pattern, rather than bringing their feet together. The maneuver was generally accompanied by a little hop or skip. In some versions, the dance ended with an exchange of kisses.

In Valhalla, Ludwig meets the ghost of Marie Antoinette in his Hall of Mirrors, and the pair do a quick gavotte - a dance which originated as a French folk dance (above, a Breton version), and took its name from the Gavot peasants of the Alpine Pays de Gap region. The gavotte is notated in 4/4 or 2/2 time, and in its original form, its musical phrases began in the middle of the bar, creating a half-measure upbeat. Dancers generally faced each other either in lines or a circle with joined hands, but steps varied widely, as did floor patterns and such pantomimes as bowing to the leader of the dance; a distinguishing feature of the gavotte, however, was that when moving sideways, dancers were required to cross their feet in a step pattern, rather than bringing their feet together. The maneuver was generally accompanied by a little hop or skip. In some versions, the dance ended with an exchange of kisses.The gavotte became popular with the nobility in the court of Louis XIV, where Jean-Baptiste Lully, the leading composer, made the dance more decorous and stately. Other composers of the Baroque period, including J.S. Bach, then incorporated the dance into the standard instrumental suite of the era. The gavotte had faded somewhat in popularity by the nineteenth century; its inclusion in Valhalla is some indication of Ludwig’s essentially backward-looking mindset – or perhaps of his awareness of the customs of Marie Antoinette's day.

Sunday, April 1, 2007

The Allies in Bavaria

The Eagle's Nest today.

It's possible, but improbable, that James and Henry Lee could have parachuted into southwestern Bavaria, as they do in the second act of Valhalla - but only because after pitched battles at Nuremberg and Munich, the prize in Bavaria was in the southeast, not the southwest - in particular, Hitler's famed mountain retreat outside Berchtesgaden. This complex, on the Obersalzberg mountainside, included his home, the Berghof, and above it, on the utmost crag, the famed Kehlsteinhaus, or Eagle's Nest (above), which was built for him by the Nazi Party on the occasion of his 50th birthday. Many believed that Berchtesgaden would be chosen by the collapsing German government as the site of its last stand (indeed, Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring was headquartered there, demanding that Hitler cede him leadership of the country). Eisenhower was so convinced this would be the Nazi endgame that once the Allies reached the Elbe, just 75 miles from Berlin, he shifted the American strategic focus from capturing the capital to conquering Bavaria, and sent the weight of American forces south, allowing the Soviets to take Berlin, which profoundly affected the balance of postwar power.

As it happened, of course, Hitler had decided to remain in his Berlin bunker; no serious plans had been made for a retreat to Bavaria. Instead, he called for the destruction of all German industry and transport, in an imagined debacle much like the climax of Wagner's Götterdämmerung; indeed, the Berlin Philarmonic chose Brünnhilde's immolation scene from that opera as their final performance before fleeing the city. But Hitler's commands went unheeded. After learning Soviet tanks were rolling down the streets of Berlin, he committed suicide on April 30, 1945. The US 3rd Infantry Division reached Berchtesgaden on May 4, and the 101st Airborne Division parachuted in on May 5; together they easily secured the area. Above, a US soldier approaches the ruins of the Berghof, which had been bombed by the RAF; the Kehlsteinhaus, taken the next day, was largely unharmed, and operates now as a restaurant.

As it happened, of course, Hitler had decided to remain in his Berlin bunker; no serious plans had been made for a retreat to Bavaria. Instead, he called for the destruction of all German industry and transport, in an imagined debacle much like the climax of Wagner's Götterdämmerung; indeed, the Berlin Philarmonic chose Brünnhilde's immolation scene from that opera as their final performance before fleeing the city. But Hitler's commands went unheeded. After learning Soviet tanks were rolling down the streets of Berlin, he committed suicide on April 30, 1945. The US 3rd Infantry Division reached Berchtesgaden on May 4, and the 101st Airborne Division parachuted in on May 5; together they easily secured the area. Above, a US soldier approaches the ruins of the Berghof, which had been bombed by the RAF; the Kehlsteinhaus, taken the next day, was largely unharmed, and operates now as a restaurant.

Saturday, March 31, 2007

Meanwhile, back in Dainsville

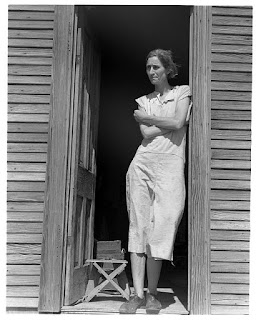

The rapid-fire text of Valhalla, with its constant shifting (and overlapping) of time and space, requires a streamlined set - yet the difference between its two main locales (Bavaria and the mythical Dainsville, Texas) is also central to its meaning and action. And therein lies one of the play's theatrical challenges: making real for the audience the phenomenal distance between the creature comforts of Ludwig II and James Avery, Paul Rudnick's fictional gay boy growing up in Texas in the 1930s. Perhaps the photograph above will help make the contrast clearer - by the famous Dorothea Lange, it's a portrait of a migrant farmer's wife in the doorway of her home near Childress, Texas, in 1938 (her three children are inside). Could this be James Avery's mother (compare and contrast Marie of Prussia, Ludwig's mother, below)?

The rapid-fire text of Valhalla, with its constant shifting (and overlapping) of time and space, requires a streamlined set - yet the difference between its two main locales (Bavaria and the mythical Dainsville, Texas) is also central to its meaning and action. And therein lies one of the play's theatrical challenges: making real for the audience the phenomenal distance between the creature comforts of Ludwig II and James Avery, Paul Rudnick's fictional gay boy growing up in Texas in the 1930s. Perhaps the photograph above will help make the contrast clearer - by the famous Dorothea Lange, it's a portrait of a migrant farmer's wife in the doorway of her home near Childress, Texas, in 1938 (her three children are inside). Could this be James Avery's mother (compare and contrast Marie of Prussia, Ludwig's mother, below)?

The Bachelor

Given his later excesses, it's easy to forget that at the start of his reign, Ludwig was quite popular (and he never entirely lost his public following). The coronation portrait by Ferdinand von Piloty (at left) gives some idea why: in his general's uniform and flowing coronation robes, the young Ludwig looks quite dashing (you can make out his crown in the shadows to his left). It's easy to see how the Empress of Austria might have nicknamed him "The Eagle," and it's no wonder eligible bachelorettes flocked to his court for a chance to become his queen.

Given his later excesses, it's easy to forget that at the start of his reign, Ludwig was quite popular (and he never entirely lost his public following). The coronation portrait by Ferdinand von Piloty (at left) gives some idea why: in his general's uniform and flowing coronation robes, the young Ludwig looks quite dashing (you can make out his crown in the shadows to his left). It's easy to see how the Empress of Austria might have nicknamed him "The Eagle," and it's no wonder eligible bachelorettes flocked to his court for a chance to become his queen.

All about his mother

Ludwig's mother was Marie of Prussia (so it's interesting that he so quickly submitted to Prussia's military will; see post below). She married Ludwig's father, Maximilian II, at 17 (he was twice her age), and gave birth to Ludwig at 19; she was also her husband's cousin. Marie was considered a socially engaged monarch, and was well-liked by Bavaria's Catholics, even though she herself was an Evangelical Protestant (not quite like today's evangelicals, however; those of Marie's day were dedicated to personal salvation and piety, and such social causes as temperance and abolitionism). While no intellectual - she once wondered aloud why anyone would spend time reading - Marie nevertheless revived the dormant Bavarian Women's Association, a service organization which eventually was taken over by the Red Cross. She had the reputation of being a well-meaning, but distant, mother - by most accounts, Ludwig found what motherly affection he came by from his governess (not dramatized in Valhalla), Sybille Meilhaus. Meanwhile Ludwig's father doted on his brother Otto, who was considered a far happier child than Ludwig, who even as a boy was perceived as inclined to romantic melancholy. To "correct" this tendency, his governess was replaced by a strict military tutor when Ludwig was nine (tellingly, he remained in touch with her for the rest of his life). After Maximilian's death, Marie converted to Catholicism, at first living with Ludwig in the castle her husband had built for them. But as Ludwig grew more eccentric, she slowly withdrew, spending more and more of her time at her own estate in the Alps. She outlived Ludwig by three years.

Ludwig's mother was Marie of Prussia (so it's interesting that he so quickly submitted to Prussia's military will; see post below). She married Ludwig's father, Maximilian II, at 17 (he was twice her age), and gave birth to Ludwig at 19; she was also her husband's cousin. Marie was considered a socially engaged monarch, and was well-liked by Bavaria's Catholics, even though she herself was an Evangelical Protestant (not quite like today's evangelicals, however; those of Marie's day were dedicated to personal salvation and piety, and such social causes as temperance and abolitionism). While no intellectual - she once wondered aloud why anyone would spend time reading - Marie nevertheless revived the dormant Bavarian Women's Association, a service organization which eventually was taken over by the Red Cross. She had the reputation of being a well-meaning, but distant, mother - by most accounts, Ludwig found what motherly affection he came by from his governess (not dramatized in Valhalla), Sybille Meilhaus. Meanwhile Ludwig's father doted on his brother Otto, who was considered a far happier child than Ludwig, who even as a boy was perceived as inclined to romantic melancholy. To "correct" this tendency, his governess was replaced by a strict military tutor when Ludwig was nine (tellingly, he remained in touch with her for the rest of his life). After Maximilian's death, Marie converted to Catholicism, at first living with Ludwig in the castle her husband had built for them. But as Ludwig grew more eccentric, she slowly withdrew, spending more and more of her time at her own estate in the Alps. She outlived Ludwig by three years.

Wednesday, March 28, 2007

Lost inside a diamond . . .

At the climax of Valhalla, Paul Rudnick offers a kind of synthesis of Ludwig's palaces rather than any kind of accurate tour. James and Henry Lee first visit the Schloss Linderhof, describing it as "a huge, demented wedding cake" and venturing into its famous underground "Venus grotto" (see post below). They later wander over to Neuschwanstein; in between, however, they seem to wake up in the Herrenchiemsee Neues Schloss ("New Palace"), Ludwig's "recreation" of Versailles (Ludwig seemed to divide his time between idolizing the mythical Lohengrin and the all-too-real Louis XIV).

This is physically impossible, as the Herrenchiemsee, as it is usually known, is on an island in the middle of the largest lake in Bavaria, and is only accessible by ferry. But what the hey - since Rudnick plays relentlessly with time, I suppose he can play with space, too. The Herrenchiemsee never reached the size of Versailles - only the central portion of the initial design, by Christian Jank, Franz Seitz, and Georg Dollman, was built - but it is obviously an imitation of the Sun King's palace, and features a similar (though not nearly as extensive) park, replete with baroque fountains and gardens. One feature of the Neues Schloss, however, actually surpassed in size its model at Versailles - the Hall of Mirrors (above). In Valhalla, the characters describe it as "like being lost inside a diamond," and the ghost of Marie Antoinette herself appears to compliment Ludwig on his creation.

This is physically impossible, as the Herrenchiemsee, as it is usually known, is on an island in the middle of the largest lake in Bavaria, and is only accessible by ferry. But what the hey - since Rudnick plays relentlessly with time, I suppose he can play with space, too. The Herrenchiemsee never reached the size of Versailles - only the central portion of the initial design, by Christian Jank, Franz Seitz, and Georg Dollman, was built - but it is obviously an imitation of the Sun King's palace, and features a similar (though not nearly as extensive) park, replete with baroque fountains and gardens. One feature of the Neues Schloss, however, actually surpassed in size its model at Versailles - the Hall of Mirrors (above). In Valhalla, the characters describe it as "like being lost inside a diamond," and the ghost of Marie Antoinette herself appears to compliment Ludwig on his creation.

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

Bavaria, Texas?

No, there's no Bavaria, Texas - but then there's no Dainsville, Texas, either. Instead, there are quite a few links between the Lone Star State and Ludwig's home, which hint at a striking similarity hidden beneath their juxtaposition in Valhalla. It goes largely unnoticed (or rather, it's been edited out of our cultural script since the two World Wars) that Germans comprise the single largest ethnic group in the U.S.; there are approximately 50 million Americans of German descent. As elsewhere in America, there was heavy German settlement in Texas - particularly in the Texas "Hill Country" - between 1848 and World War I, and today there's a similar conservative, religion-centered, and not very gay-friendly culture in both locales. Likewise, both Texas and Bavaria tend to view themselves as something like virtual nation-states within their larger countries' borders. Indeed, many Texans will tell you that "Bavaria is Germany's Texas," and some Bavarians have been known to favor cowboy hats. In the last few decades, Texans have adopted such Bavarian traditions as Oktoberfest with a vengeance; some say one of the largest Oktoberfests outside Munich is in Fredericksburg, Texas, which also hosts a German shooting festival, or Schuetzenfest. There's even a Texan dialect of German, which is now only spoken by a few septagenarians in the Hill Country west of Austin.

Did Princess Sophie really have a hump?

Playwright Paul Rudnick says she did - and gives her a charmingly rueful characterization based on her savvy sense of her own "difference" in the image-driven world of Ludwig's court. Indeed, perversely enough, it's her very awareness of her lack of conventional beauty - her incipient sense of camp - that endears her to the gay Ludwig.

Playwright Paul Rudnick says she did - and gives her a charmingly rueful characterization based on her savvy sense of her own "difference" in the image-driven world of Ludwig's court. Indeed, perversely enough, it's her very awareness of her lack of conventional beauty - her incipient sense of camp - that endears her to the gay Ludwig.But is Rudnick exaggerating what may have only been a slight abnormality? The photographic evidence for said hump is slim - of course the photos may have been doctored; but Sophie looks pretty normal above, in a photograph with Ludwig taken during their engagement. (For more images of Sophie, check here.)

Born Sophie Charlotte Augustine de Wittelsbach, Sophie was officially a Duchess of Bavaria; an alliance with Ludwig would have been a big step up, and would have put her on a nearly-equal social footing with her sister, Elisabeth, who was now Empress of Austria and had also been close friends with Ludwig. Clearly, unlike the character she inspired in Valhalla, Sophie was serious about the matrimonial sweepstakes; she married Ferdinand Philippe Marie, duc d'Alençon, in 1868, the year after she was dumped by Ludwig, and promptly had two children. So no flies on her, hump or not.

One last note about the gallant Duchesse d'Alençon. She was caught in a famous fire, at a charity bazaar in Paris in 1897; but when rescuers tried to carry her away from the flames, she insisted other women and children be saved first, stating "Because of my title I was the first to enter here, and I shall be the last to go out." Sophie perished in the subsequent inferno, at age 50.

One last note about the gallant Duchesse d'Alençon. She was caught in a famous fire, at a charity bazaar in Paris in 1897; but when rescuers tried to carry her away from the flames, she insisted other women and children be saved first, stating "Because of my title I was the first to enter here, and I shall be the last to go out." Sophie perished in the subsequent inferno, at age 50.

Monday, March 26, 2007

Inside Ludwig's Castles

When James and Henry Lee parachute behind enemy lines at the climax of Valhalla, they stumble onto (or into) two of Ludwig's castles, the Schloss Linderhof and Neuschwanstein (which are a few miles apart in southwestern Bavaria). As you can see from the following photographs, playwright Paul Rudnick has hardly exaggerated the extravagance of these castles' interiors (although in general, Neuschwanstein is underdecorated; only fourteen rooms, on the third and fourth floors, were completed before Ludwig's death; the first and second floors are largely bare brick to this day).

Neuschwanstein is comprised of a gatehouse, a "Bower," the Knight's House with a square tower, and a Palas, or citadel (above), with two towers to the Western end. On the exterior, it is a fanciful pastiche of medieval and Romanesque elements; its interior, however, was intended as an even more flamboyant evocation of the chivalric ethos of Richard Wagner's operas.

The rooms within the Palas that were finished by Ludwig are so overdecorated as to be almost overwhelming; the Throne Room (above) in particular was intended to resemble the legendary Grail-Hall of Parsifal (father of Lohengrin), and so was designed in an elaborate Byzantine style by Eduard Ille and Julius Hofmann. Inspired by the Hagia Sophia, the two-story Throne Room was only completed in the year of the king's death; the throne itself was never made.

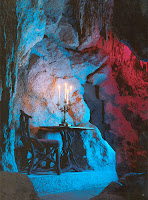

The Grotto, which was not underground, as one might expect, but was located between Ludwig's living room and his study, was one of the most unusual rooms in Neuschwanstein, and was used by the increasingly-isolated king as a refuge in which to indulge his melancholy moods. Its artificial stalactites were built of oakum and plaster-of-Paris by the famed landscape sculptor Dirrigl of Munich. Dirrigl had already built a far more extragant grotto in the park of the Schloss Linderhof. This artificial lake was designed as a kind of real-life stage set for the "Venus Grotto" scene from Wagner's Tannhäuser (see below). It is in this underground boudoir, with its far more erotic atmosphere, that James and Henry Lee first encounter Ludwig's legacy in Valhalla.

The Grotto, which was not underground, as one might expect, but was located between Ludwig's living room and his study, was one of the most unusual rooms in Neuschwanstein, and was used by the increasingly-isolated king as a refuge in which to indulge his melancholy moods. Its artificial stalactites were built of oakum and plaster-of-Paris by the famed landscape sculptor Dirrigl of Munich. Dirrigl had already built a far more extragant grotto in the park of the Schloss Linderhof. This artificial lake was designed as a kind of real-life stage set for the "Venus Grotto" scene from Wagner's Tannhäuser (see below). It is in this underground boudoir, with its far more erotic atmosphere, that James and Henry Lee first encounter Ludwig's legacy in Valhalla.

The Venus Grotto at Schloss Linderhof.

Sunday, March 25, 2007

Lohengrin and the Holy Grail

Lohengrin (at left, from a nineteenth century postcard) first appears in the written record as "Loherangrin," the son of Parzival, the Grail King, in the epic Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach (1170-1220). The Knight of the Swan story was part of a long oral tradition associated with Godfrey of Bouillon, but von Eschenbach was the first to tie the tale to the Arthurian legend of the Holy Grail. In this version of the story, Loherangrin serves his father as one of the Grail Knights, who are sent out in secret to guard kingdoms that have lost their protectors. Loherangrin is eventually called to this duty in Brabant, where the duke has died without a male heir. The duke's daughter Elsa fears the kingdom will be lost, but Loherangrin arrives in a boat pulled by a swan and offers to defend her, though he warns that she must never ask his name. They fall in love and eventually wed, but one day Elsa asks what she knows is verboten. The Swan Knight answers, but then regretfully steps back onto his boat, never to return.

Lohengrin (at left, from a nineteenth century postcard) first appears in the written record as "Loherangrin," the son of Parzival, the Grail King, in the epic Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach (1170-1220). The Knight of the Swan story was part of a long oral tradition associated with Godfrey of Bouillon, but von Eschenbach was the first to tie the tale to the Arthurian legend of the Holy Grail. In this version of the story, Loherangrin serves his father as one of the Grail Knights, who are sent out in secret to guard kingdoms that have lost their protectors. Loherangrin is eventually called to this duty in Brabant, where the duke has died without a male heir. The duke's daughter Elsa fears the kingdom will be lost, but Loherangrin arrives in a boat pulled by a swan and offers to defend her, though he warns that she must never ask his name. They fall in love and eventually wed, but one day Elsa asks what she knows is verboten. The Swan Knight answers, but then regretfully steps back onto his boat, never to return.In 1848 Richard Wagner adapted the tale into his wildly popular opera Lohengrin,the work through which the story is best (perhaps solely) known today. In the opera, Lohengrin appears on his favorite mode of transport to defend Princess Elsa from the false accusation of killing her brother (who turns out to be alive and well at the end of the opera). Intriguingly, Wagner extends the theme of the Holy Grail, and its symbolism of masculine purity, further into the story by adding an explanation for Lohengrin's keeping his true identity in the closet: the Grail, recovered by Lohengrin's father, imbues the Knight of the Swan with mystical powers that can only be maintained if their source remains unspoken. The most famous piece from Lohengrin is the "Bridal Chorus" (now familiar as "Here Comes the Bride"), which accompanies the marriage of Lohengrin and Elsa; one of the shorter Wagnerian works, the opera remains a staple of the modern stage.

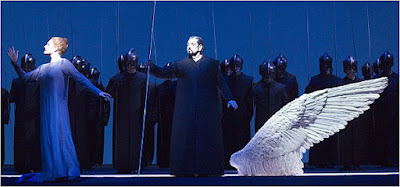

Robert Wilson's recent production of Lohengrin for the Metropolitan Opera.

Ludwig, Wagner, Swans, and Castles

One of Ludwig's first royal acts was to become an official patron of Wagner, and he invited the composer to visit his court, despite Wagner’s controversial political past, and what was perceived as the “radicalism” of his operas.

One of Ludwig's first royal acts was to become an official patron of Wagner, and he invited the composer to visit his court, despite Wagner’s controversial political past, and what was perceived as the “radicalism” of his operas. Wagner’s Lohengrin, with its Swan Knight hero, had particularly captured the young king’s fancy, and no wonder - his childhood home, Schloss Hohenschwangau (below), was built by Ludwig's father, Maximilian, on the remains of the fortress Schwanstein (or “Swan Stone” Castle), which was first mentioned in records from the 12th century. Legend had it that a family of knights was responsible for its construction. After the demise of their order in the 16th century, the fortress changed hands several times, and had fallen into ruin by the time Maximilian ascended the throne.

Schloss Hohenschwangau, built on the ruins of the legendary Schwanstein.

Ludwig's awareness that his home was built on the ruins of this legendary fortress would eventually combine with his obsession with Lohengrin to produce his greatest architectural folly - the castle later known as Neuschwanstein ("New Swan Stone" Castle). Ludwig outlined his vision in a letter to Wagner, dated 13 May 1868; "It is my intention to rebuild the old castle ruin at Hohenschwangau near the Pollat Gorge in the authentic style of the old German knights' castles...the location is the most beautiful one could find, holy and unapproachable, a worthy temple for the divine friend who has brought salvation and true blessing to the world." The foundations of the building were laid on September 5, 1869 - although Ludwig would not live to see the project completed. Neuschwanstein was designed by Christian Jank, a theatrical set designer, which explains much of its fantastic decoration. Despite its faux-medieval appearance, however, the castle was built on a steel frame and came outfitted with every modern convenience. During Ludwig's life, the building was known as "New Hohenschwangau Castle"; it was only after his death that the name "Neuschwanstein" became popular, melding Ludwig's identity with that of the Swan Knights.

Neuschwanstein today.

King Ludwig II, Part I

A central figure in Valhalla,King Ludwig II of Bavaria was born in 1845, the son of King Maximilian II of Bavaria and Princess Marie of Prussia. He was extremely spoiled as a child, and constantly reminded of his royal power; but he was also often subjected to ruthless regimens of exercise and study. The happiest days of his childhood were spent at Lake Starnberg (the eventual site of his death), and Schloss Hohenschwangau, the castle built by his father in the foothills of the Alps.

A central figure in Valhalla,King Ludwig II of Bavaria was born in 1845, the son of King Maximilian II of Bavaria and Princess Marie of Prussia. He was extremely spoiled as a child, and constantly reminded of his royal power; but he was also often subjected to ruthless regimens of exercise and study. The happiest days of his childhood were spent at Lake Starnberg (the eventual site of his death), and Schloss Hohenschwangau, the castle built by his father in the foothills of the Alps.Teenaged Ludwig became best friends with (and possibly the lover of) his aide de camp, the handsome aristocrat and sometime actor Paul Maximilian Lamoral, a scion of the wealthy Thurn and Taxis dynasty. The two young men rode together, read poetry aloud, and staged excerpts from the operas of their idol, Richard Wagner. Their relationship lapsed when Paul eventually became more interested in (or at least began courting) young women. During these years Ludwig began a lifelong friendship with his cousin Duchess Elisabeth, who eventually married Franz Joseph to become Empress of Austria. The two teenagers loved nature and poetry, and nicknamed each other “the Eagle” (Ludwig) and “the Seagull” (Elisabeth).

In 1864, King Maximilian died, and Ludwig inherited the throne at 18. He took the royal apartments in Schloss Hohenschwangau as his own, but did not displace his mother - as he never married, she retained her customary rooms in the castle. By 1867, Ludwig had become engaged to Princess Sophie, his cousin and Empress Elisabeth's younger sister, but after repeatedly postponing the wedding, Ludwig cancelled the engagement that October. Ludwig never married - instead he was linked romantically to a number of men, including his chief equerry Richard Hornig, Hungarian theatre star Josef Kainz, and courtier Alfons Weber. (Sophie eventually married Ferdinand Philippe Marie, duc d'Alençon, but died some twenty years later in a fire which destroyed the Paris Charity Bazaar.)

That same year, Ludwig underwent (and failed) his most serious test as a monarch; he sided with Austria against Prussia in the Seven Weeks' War, and was forced to accept a mutual defense treaty with Prussia after Austria's defeat. Under the terms of this treaty, Bavaria joined with Prussia against France in the Franco-Prussian War. Ludwig received some concessions in return for his support, but essentially he had lost his independence. Stripped of true responsibility for his kingdom, Ludwig began to recede further into a life of royalist fantasy. He was only 22.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)